Encountering Mughal Women was a month-long project in July 2020 for an artist residency titled “The Untold Edition.” I worked with one text, the Humayunnama, a historical account of early Mughal India, penned by Gulbadan Begum (d. 1603). Gulbadan Begum was the daughter of Babur, who founded the empire that is now known for the Taj Mahal. Babur wrote an autobiography and his daughter followed in his footsteps.

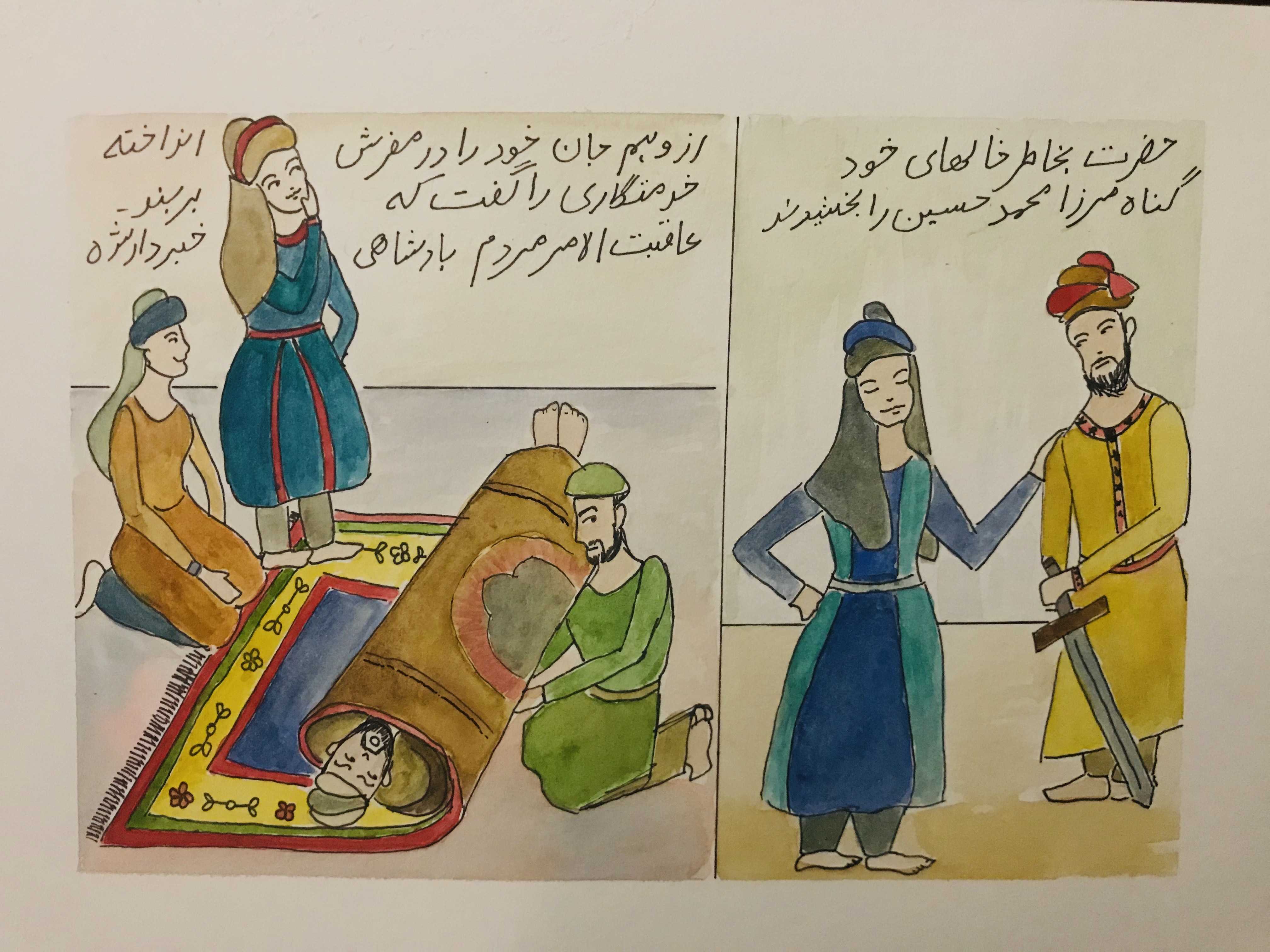

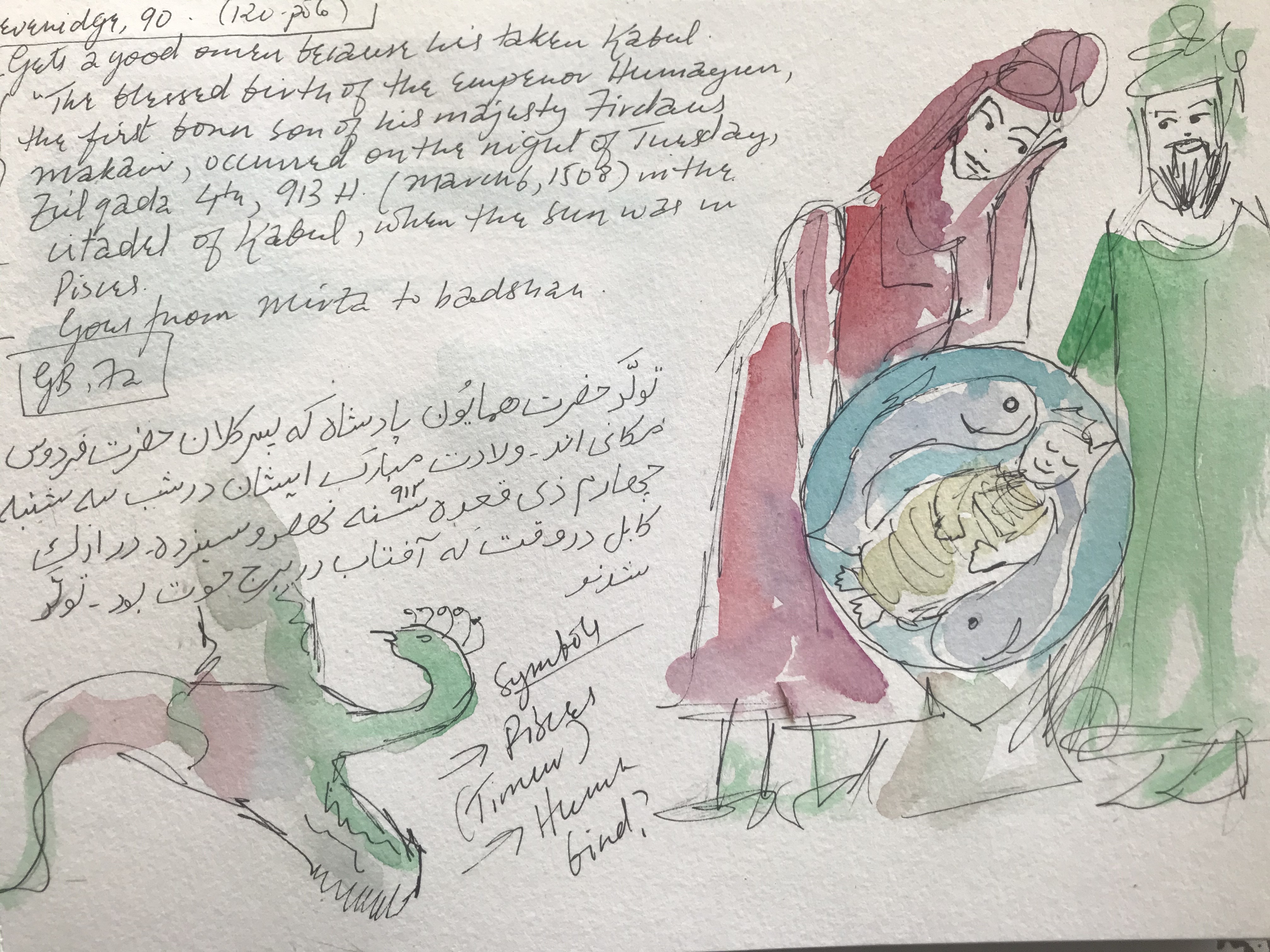

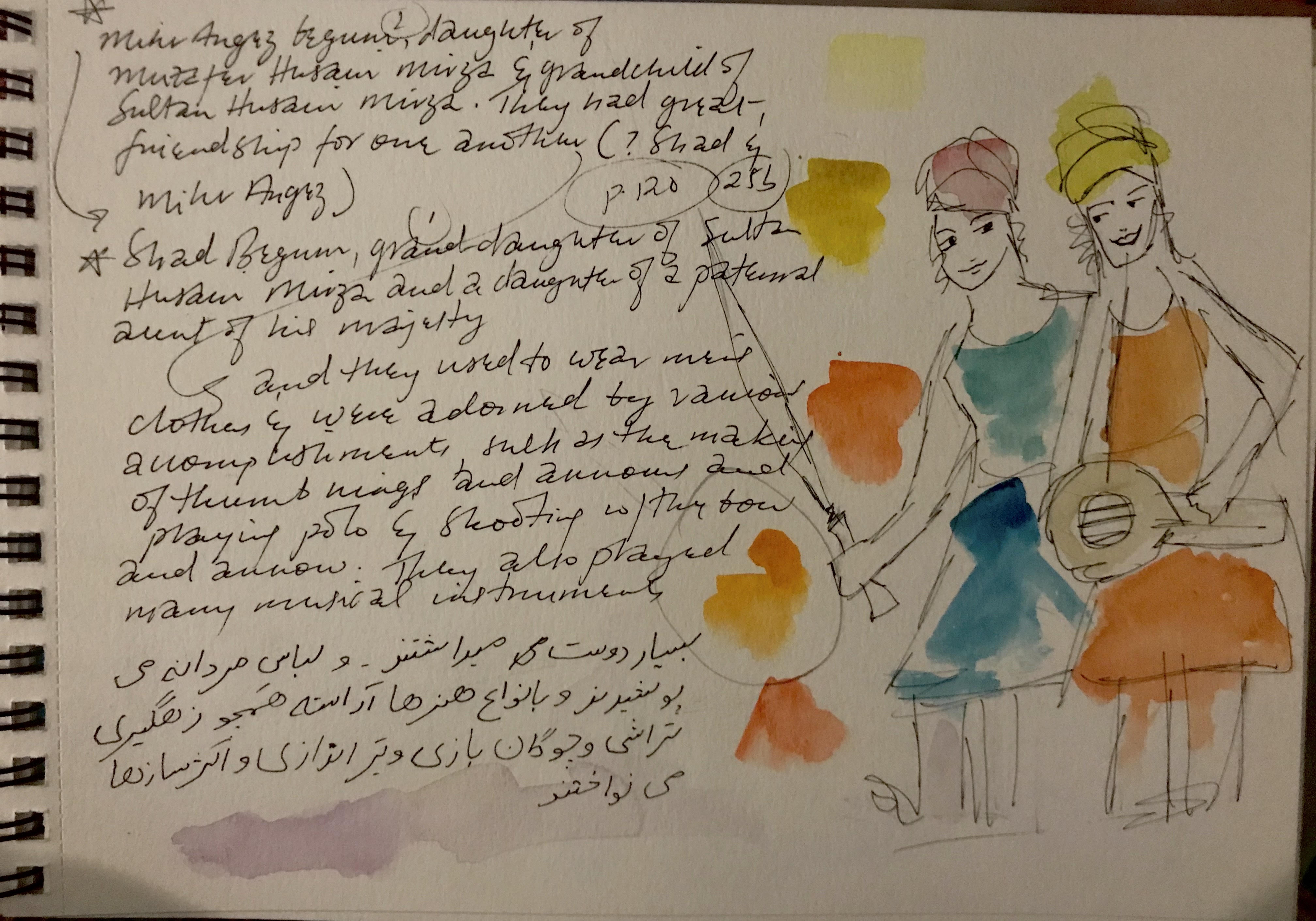

As a historian, I’ve engaged with Mughal women’s lives only through the written word; I’ve read Gulbadan Begum and written about her and I’ve published articles about Mughal women and gender in Islamic history. For “The Untold Edition,” I decided to engage with Gulbadan’s text, the Humayunnama though a different, more tactile medium. I wanted to illustrate scenes from the text using a style of illustration that would work in a children’s book. While my Instagram has finished sketches, this blog also shows the process of making my illustrations and includes thoughts about the connection between word and image, history and storytelling.

Why Gulbadan Begum?

I chose Gulbadan Begum because her text is full of scenes from everyday life, and it’s easy to imagine these scenes. Her Humayunnama is a rare instance of a Mughal text penned by a woman and since I already know it quite well, and have spent a lot of time wandering around Mughal India in my head, it’s easy to dive into her writing. Also, and this is probably my primary reason for choosing her, she’s simply not well-known, and I think she should be.

When I ask students to name a woman from the Mughal Empire, the first name they come up with is Anarkali, the doomed dancing-girl allegedly killed by the emperor Akbar (d. 1605) because he didn’t want her to marry his son, Prince Selim, who later became the emperor Jahangir (d. 1627). Anarkali probably didn’t exist, even though her story is famous, especially because of Bollywood. Other women who come up all have one thing in common: They are the objects of male love or desire. There’s Nur Jahan (d. 1645), Jahangir’s wife, and Mumtaz Mahal (d. 1631), the woman for whom Shah Jahan (d. 1666) built the Taj Mahal.

No one names Mughal women such as Gulbadan Begum. Nor do they mention Hamida Banu Begum, the wife of Humayun (d. 1556), who commissioned Humayun’s tomb, and whose design was one of the blueprints for the Taj Mahal.

Both men and women built tombs for spouses and parents; there was nothing unusual about Shah Jahan doing so for his wife. The more interesting story is that the Taj Mahal was based on a design chosen by one of Shah Jahan’s female ancestors. But since women are only interesting as objects of love, and not as subjects in themselves, this story is left untold. As Virginia Woolf puts it in “A Room of One’s Own”—women hold power and importance in male imagination, but are denied importance in the absence of a male gaze. I remember presenting a paper at an academic conference about Gulbadan’s view of history and being asked questions about her love life by two male scholars; one white, one brown, and both holders of PhDs. There are so many more things to say about women.

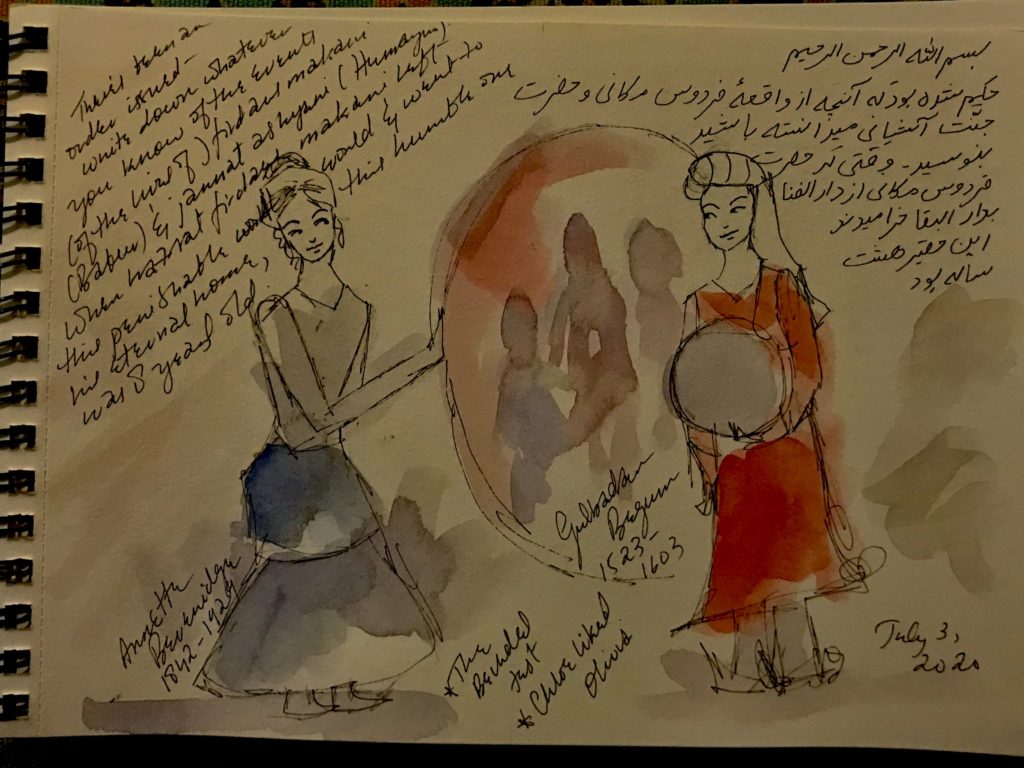

Week 1: Translation–Annette Beveridge (d. 1929) and Gulbadan Begum (d. 1603)

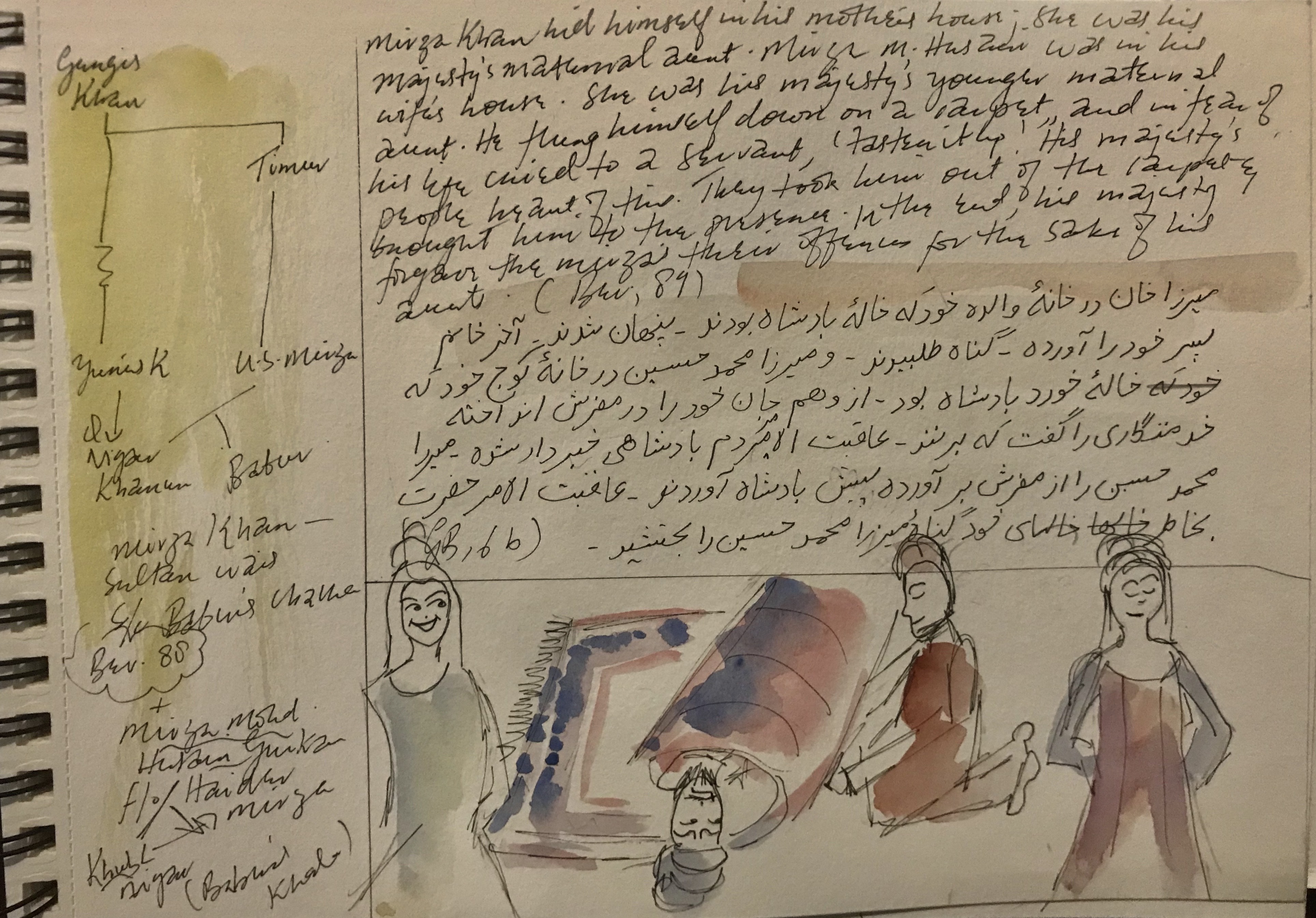

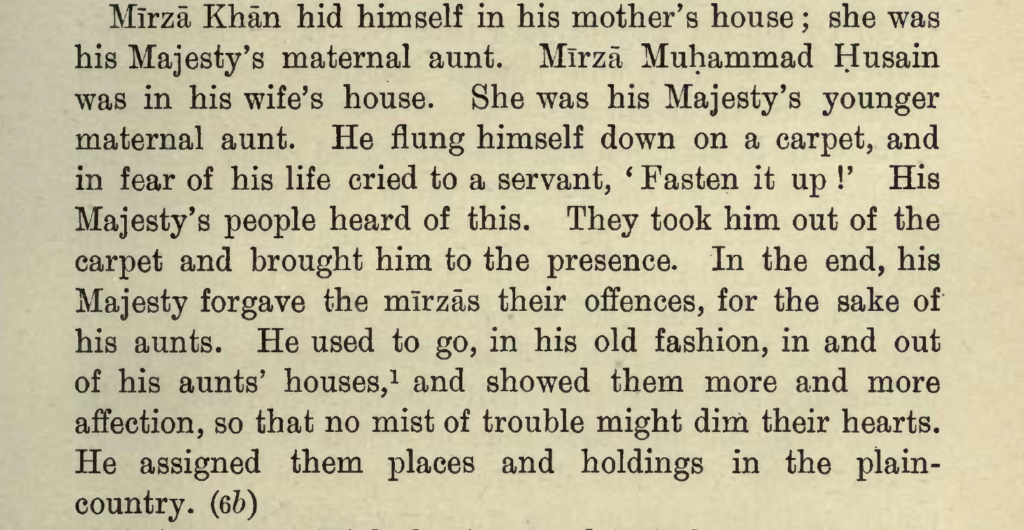

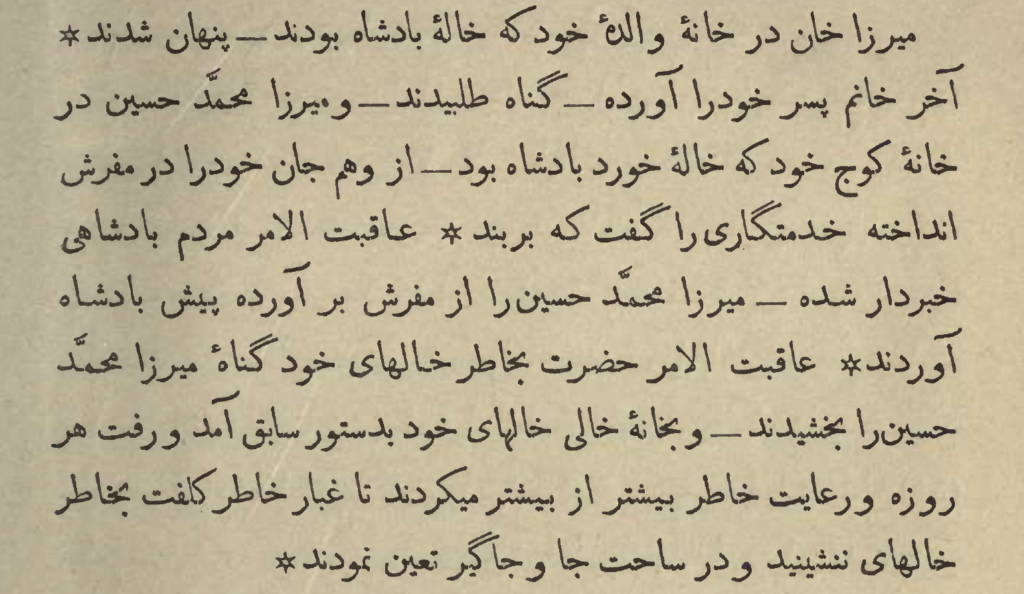

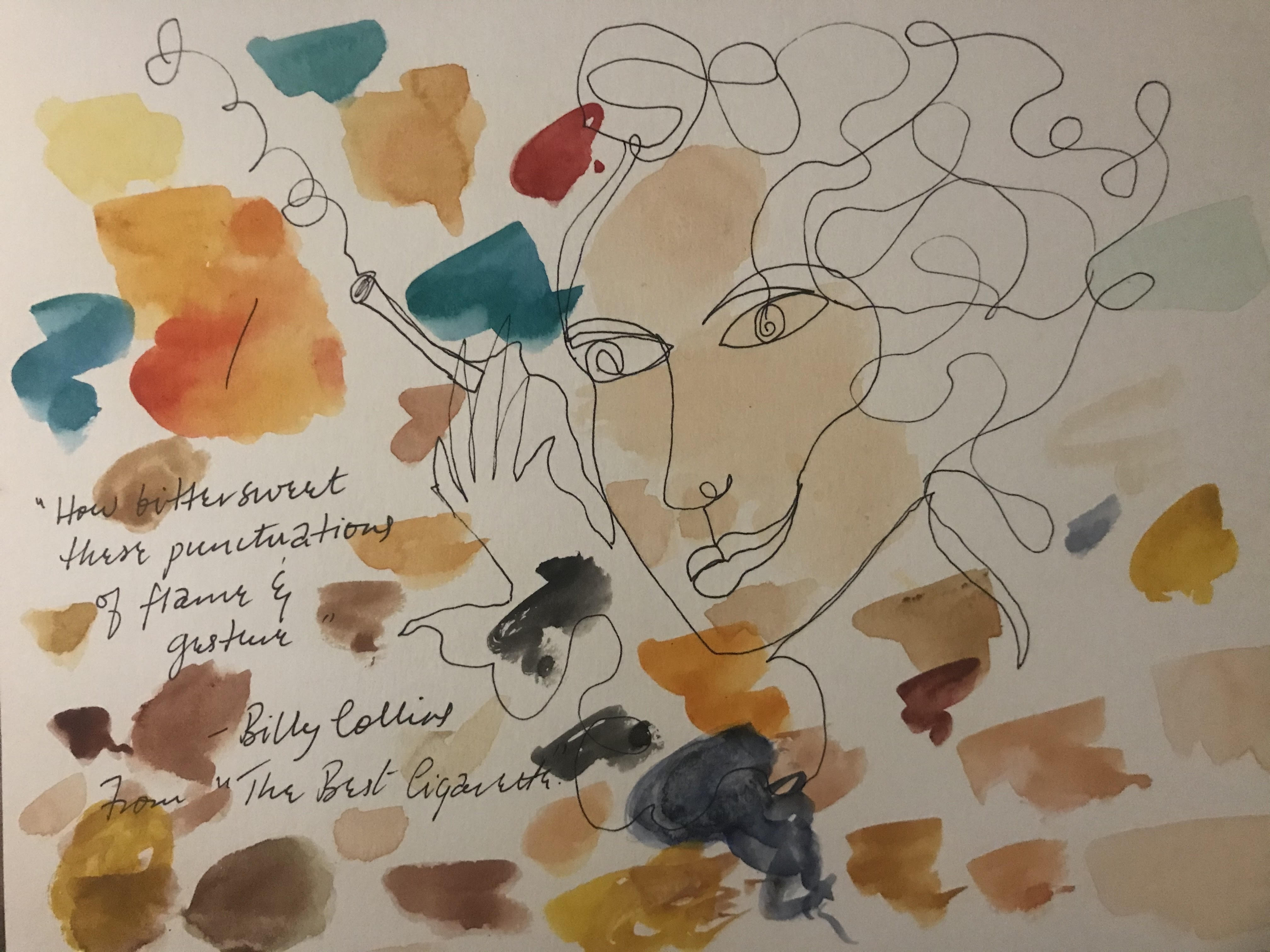

How do we know about Gulbadan? Gulbadan’s history of her brother Humayun now exists as an incomplete manuscript penned in Persian/Farsi. The manuscript was translated to English by Annette Beveridge (d. 1929) an Orientalist scholar in British India. Her husband Henry Beveridge was in the Indian Civil Service and an Orientalist scholar himself. For the first week of the project, I got interested in how a British woman encountered a Mughal woman. Did she feel an affinity with her or did she see her as foreign? My own positioning was interesting too. I think mostly in English, but I grew up on the land the Mughals ruled. This means I feel a cultural affinity with Gulbadan but speak the same language–literally!– as Beveridge. I liked reading about Gulbadan through a female translator. It was a Chloe-liked-Olivia moment. My preliminary sketch is below; I imagined some sort of crossing between worlds and tried to see how I’d go about drawing that.

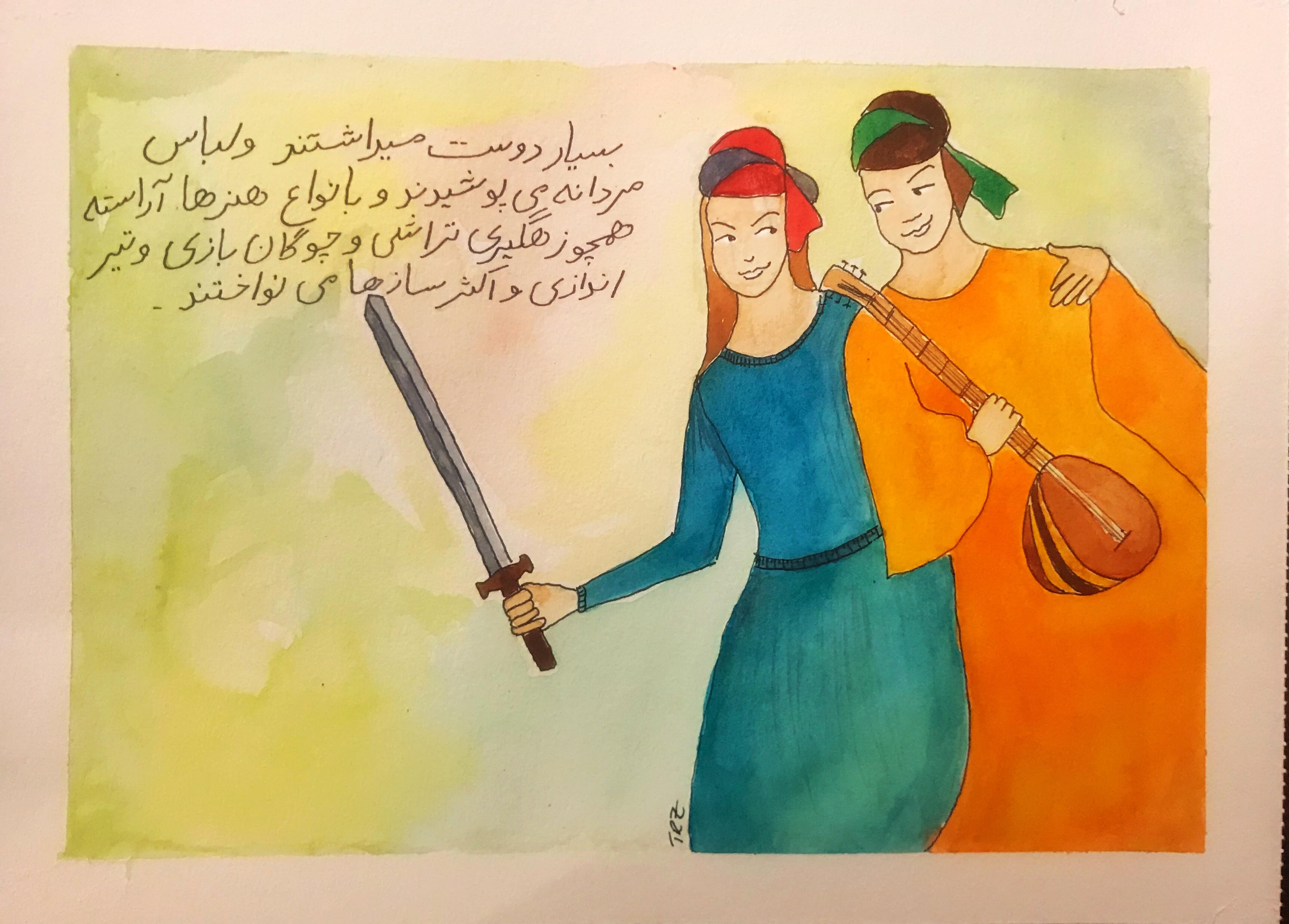

In my reading, I noticed that Annette Beveridge writes of Gulbadan with affection and admiration. She spent so much time with the text that she felt she knew Gulbadan. Beveridge writes, “She becomes a friend, even across the bars of time and creed and death.” I decided to translate this line to Farsi, the language Gulbadan would have understood had Beveridge been able to speak to her. The line that appears on my painting below is a translation. I am grateful to my Iranian friend Reihaneh Fakourfar for making my literal translation more poetic!

Notes: This took a while and I think the proportions are off. I started with ink, which didn’t sit too well on this paper. Then I tried to cover up some mistakes with watercolor. Then I added color pencil followed by ink washes. I like the idea behind this but may want to do another version sometime. I’m happy with the turquoise because there is no situation in life in which I’m not happy with turquoise!