Gulbadan Begum writes short biographical notes about the women in her circle; these tell us about a woman’s family, her skills, and what she received as her share in the spoils of war. Gulbadan’s writing is not different in this from her father’s; he too provides his readers with biographical notes about the people he knows. Quite often my students–on reading Gulbadan–cannot tell whether her text is written by a woman or a man. This leads to interesting discussions. Do women write differently? Or, does expecting them to do so, say more about us than it does about them? For instance, students are surprised when they come to the realization that they expect male-authored texts to focus on war and female-authored texts to focus on family. Gulbadan’s focuses on both, and as we’ve learned, nothing was more political than family. If there’s little difference between male and female writing in Mughal India, it means we need to ask how the Mughals differentiated gender.

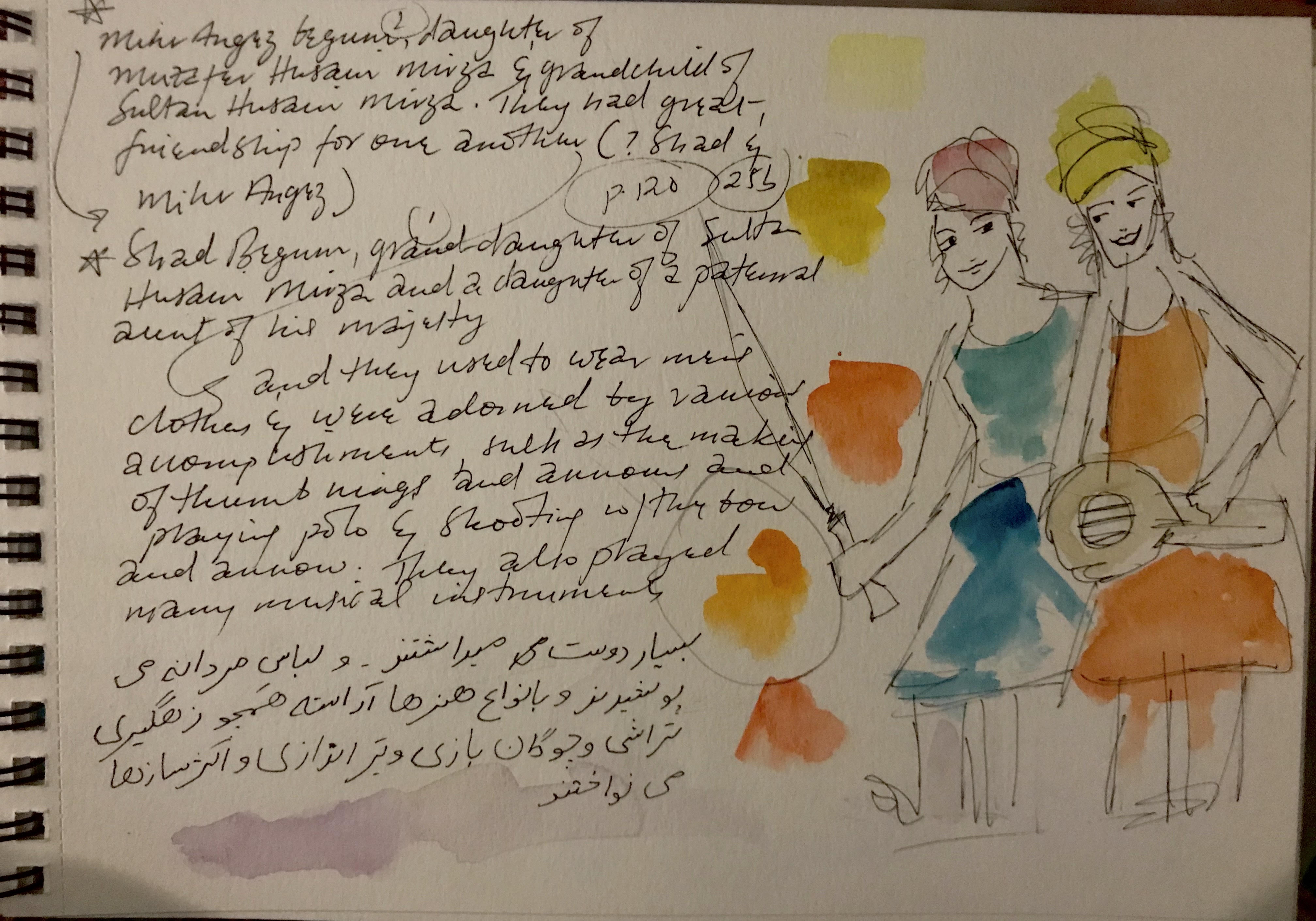

In her biographical notes, Gulbadan mentions two women, Mihr Angez Begum and Shad Begum who “had a great love/affection for one another.” They used to wear men’s clothes, she writes, and had many accomplishments. The women played polo, shot bows and arrows, and they were also skilled musicians. Close bonds between women in Mughal India weren’t unusual; both men and women inhabited largely homosocial worlds in a society in which heterosexual marriage was nonetheless seen as an important duty they had to fulfill. In his memoir, Babur writes about falling in love with a boy called Baburi; the infatuation leads him to write some poetry and wander around lovesick, and the poetic tradition with which the Mughals were familiar is filled with homoerotic encounters between men. We can conclude that women’s worlds carried the possibility of similar attachments, similarly charged intimacies. So I imagined these two women to be part of Gulbadan’s world; maybe other women thought of them as those two who were always together, and maybe they admired them for their skills and their adventures, and maybe they sat around them when they played their instruments and laughed at their jokes. In my preliminary sketch, they looked conspiratorial, knowing, and playful :

Trying to draw these women made me aware of gender fluidity in a more tangible way than just reading about it. For one, male and female figures are not dressed all that differently in Mughal art; nor are their bodies rendered all that differently. What differentiates men and women is usually breasts and facial hair. I knew I wanted to draw one woman with a weapon (I like swords more than bows and arrows!) and another with a musical instrument, but how was I to make sure they didn’t look like two men, or–horrors!–a man and a woman?

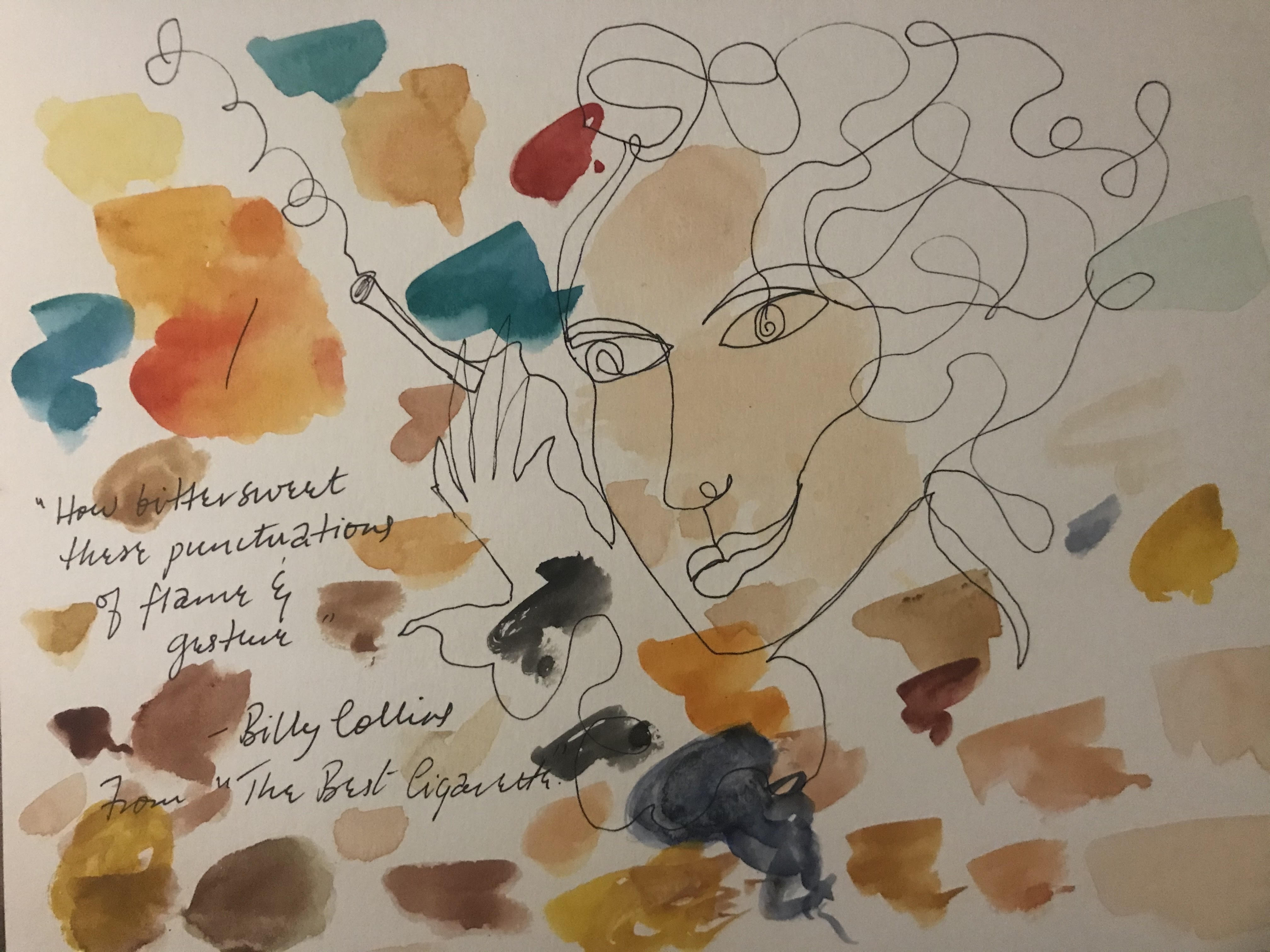

In Women with Moustaches and Men without Beards, Afsaneh Najmabadi writes about the gender fluidity present in pre-modern Persian art and of how this same art was heterosexualized as a consequence of the European gaze. Iranians, realizing that Europeans saw Iranian men as weak, effeminate, and homosexually inclined, began emphasizing heterosexuality in their art in ways they had not before. I wanted what I drew to have some of the fluidity Najmabadi mentions–her argument is relevant to India as well–and I wanted to use warm tones, so I settled on a citrusy palette.

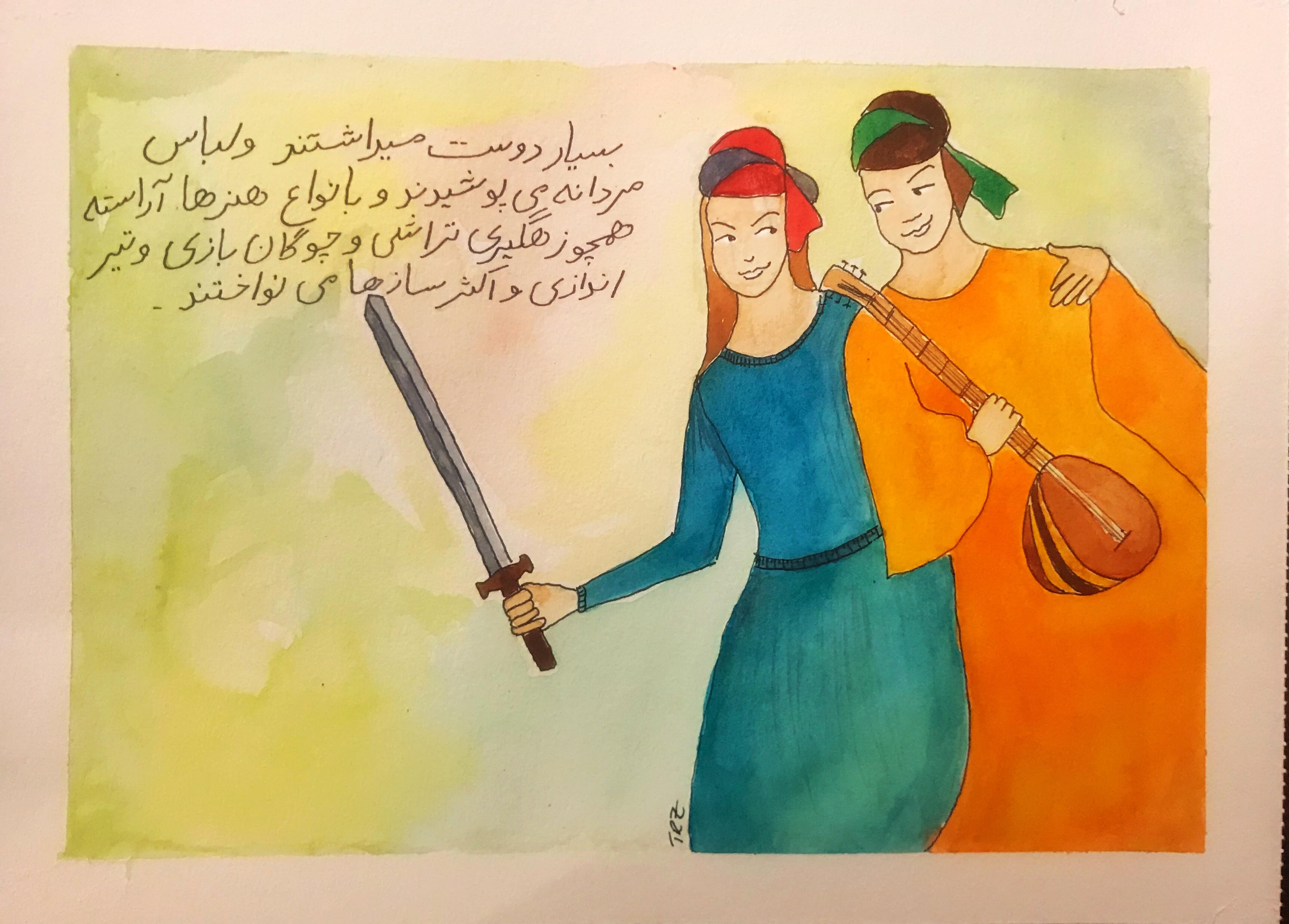

And here’s my final sketch: