If you do a Google Images search for “harem,” you’ll be awash in images of women who seem to have nothing better to do all day than lounge on beds or periodically get up to dance (not a bad life, but still!). Exhibit A:

Edward Said’s Orientalism addresses the degree to which these portrayals of non-European cultures were steeped in colonial imagination and far from reality. I routinely run into history books in which–usually when addressing the decline of an empire–a historian throws up his hands and says well, there were wars, economic crises, political mistakes, and then there was harem intrigue. The women were scheming too much, they made kings indolent, and then everything fell apart. Lazy kings also spent too much time in the harem (according to this line of argument), when they should have been out on the battlefield. Let’s correct these misconceptions.

- As historian Leslie Peirce argues, the word “harem” comes from the Arabic root H-R-M, which refers to what is sacred, protected, and forbidden. The reason the king’s household was called the harem was because kings were seen as sacred and the king’s inner sanctum, the “harem” was the most sacred space of all. The word had nothing to do with women; rather it had to do with the sanctity of the king’s body.

- Both men and women gained and lost power within the household and it was in the interests of everyone to maintain their power. This means that the household/harem wasn’t a private place where the king could retreat from his public political life; the harem was the most political place of all.

- Women and men in the Mughal Empire played active political roles. Mughal texts reveal especially the role played by senior women–mothers and aunts–in negotiating alliances, advising kings, and in many cases, preventing conflict before it happened. Babur is at pains to point out how respectful he was to his mother and his aunts and Gulbadan Begum, in her writing, does the same.

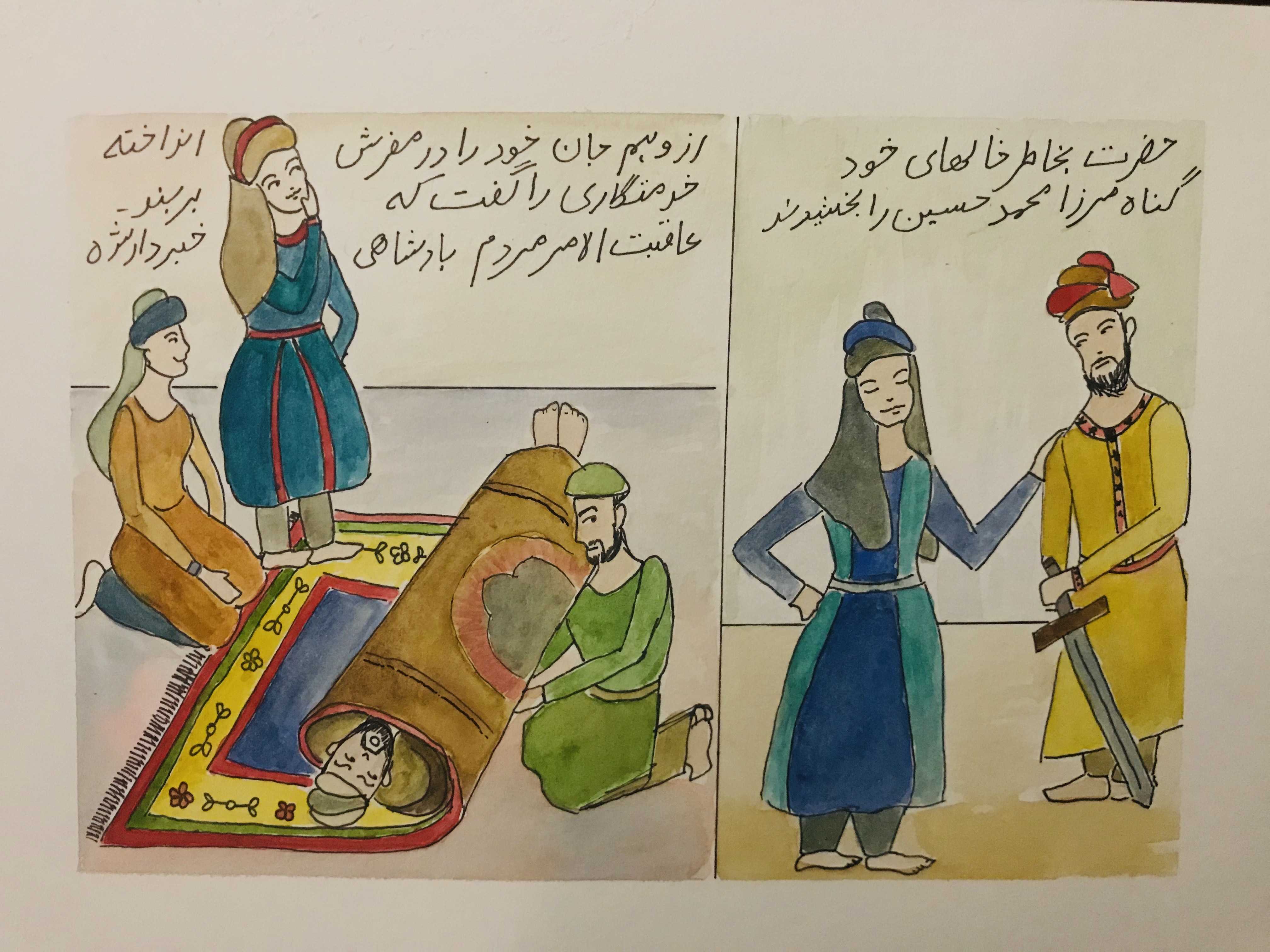

For the second week of my residency, I focused on an incident that makes me laugh. While making his bid for power in Central Asia, Babur faced opposition from his cousins. Gulbadan narrates how two of his cousins, after rebelling against Babur, were spared his wrath because Babur’s maternal aunts intervened. One of them had to be dragged out of a rug in which he was hiding. I think about how this family anecdote must have been remembered. Did the old women of the family sit together and laugh about that time when the Mirza hid in a rug? Did Gulbadan, who was just a child when Babur died, hear it from the older women, so that–when she was writing as an old woman herself–she jotted down what she remembered? Did writing it make her smile? I imagine the women sitting together and chuckling over their hot-headed sons and then shaking their heads and getting on with the task of managing them.

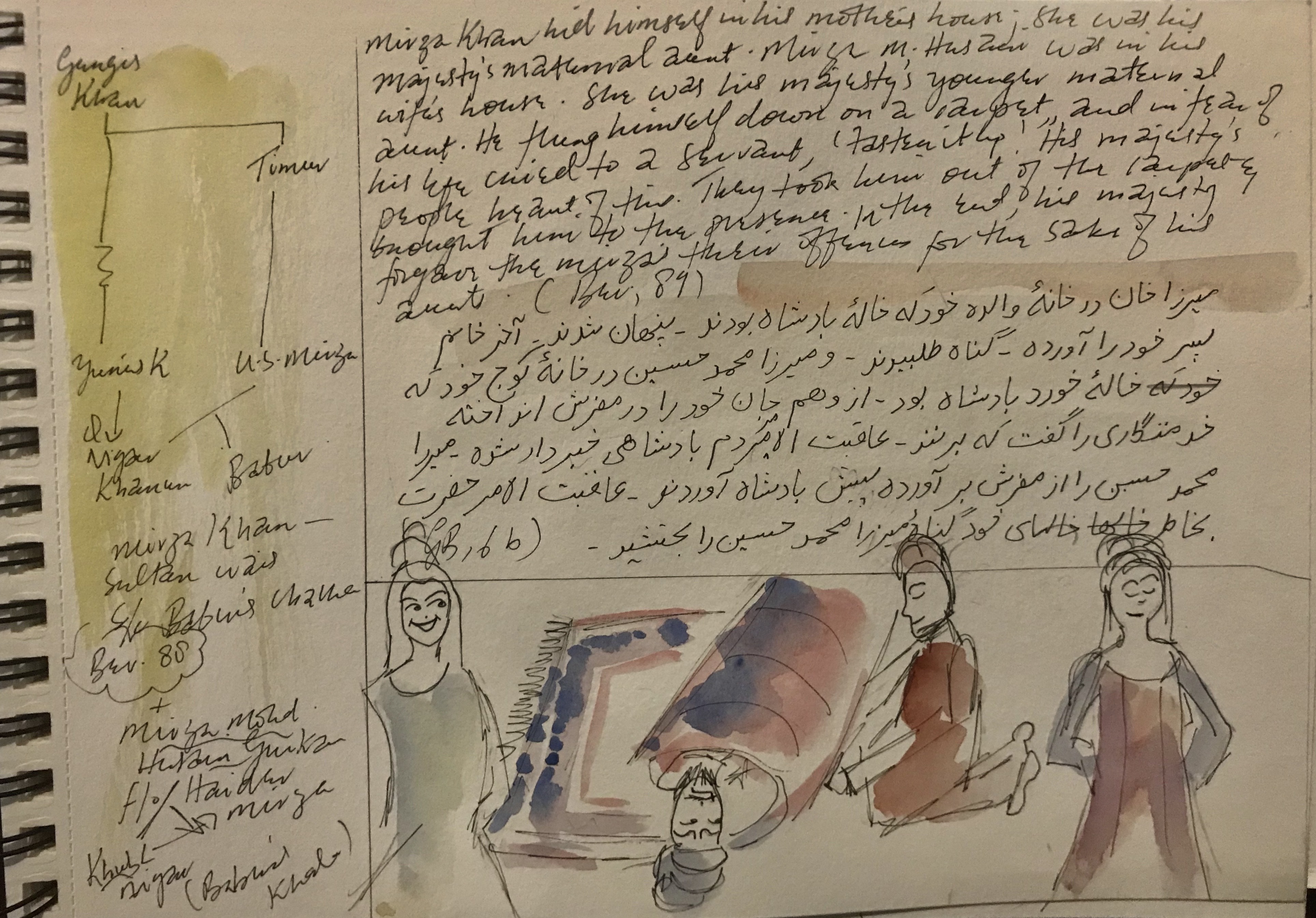

I wrote down Gulbadan’s narrative in Farsi so I could feel how her hand would have formed the words she was writing and then I drew some preliminary sketches. I can never keep my Mirzas straight, so I drew a rough family tree too. There’s something about writing in Farsi as opposed to just reading it that brings me closer to the text and to Gulbadan Begum. This is the language in which Gulbadan thought about her past, and these are the letters her hand knew how to shape; always, Beveridge’s English reads faster for me, but I keep coming back to the Farsi, which feels familiar in a different way, close as it is to Urdu, my mother tongue.

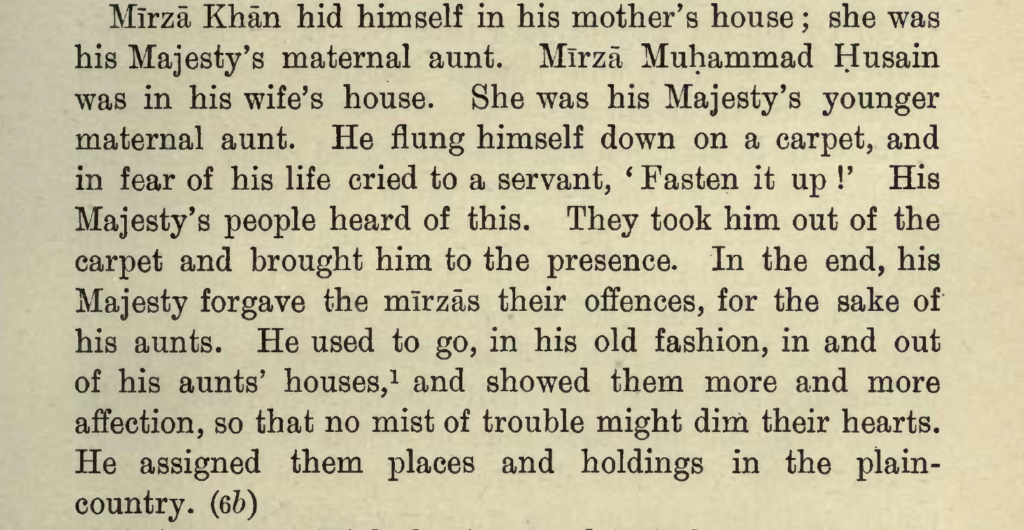

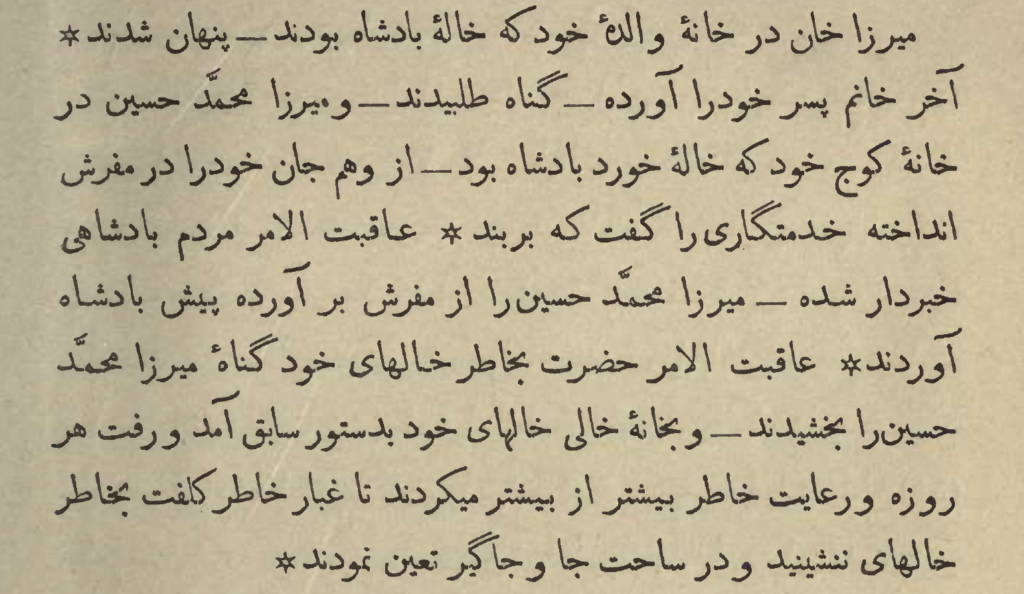

Here is Beveridge’s translation along with Gulbadan’s original:

And here is how I imagined what transpired. I drew the images first and separated the frames for them. Then I put in relevant text in Farsi.